1. Introduction: The Cosmic Order

Ancient Egyptians had a deep fascination with the cosmos. Their world was not just the land they lived on but also the vast, mysterious universe above and below. Egyptians believed in a strict order that governed all existence, a concept they called *Ma’at*. This cosmic harmony was reflected in the balance of nature, justice among people, and even the movements of stars and planets. The celestial realm, for them, was a mirror reflecting the earthly world, a divine blueprint for the world they knew.

2. The Celestial Vault: The Sky as a Physical Structure

The Egyptians envisioned the sky as a solid, arched dome, a vast ceiling stretching over the earth. This dome, often described as a “Nut” goddess, was supported by immense pillars or towering mountains, holding back the celestial waters above. The sun god Ra, a radiant disc, embarked on his daily journey across this celestial vault, bringing light and warmth to the world. His journey started in the east, where he rose from the primordial waters, traveled across the sky during the day, and descended into the west at sunset, where he sailed through the underworld or *Duat*, emerging again in the east at dawn. This celestial voyage was a constant reminder of the cyclical nature of life and death, and the eternal renewal of light and darkness.

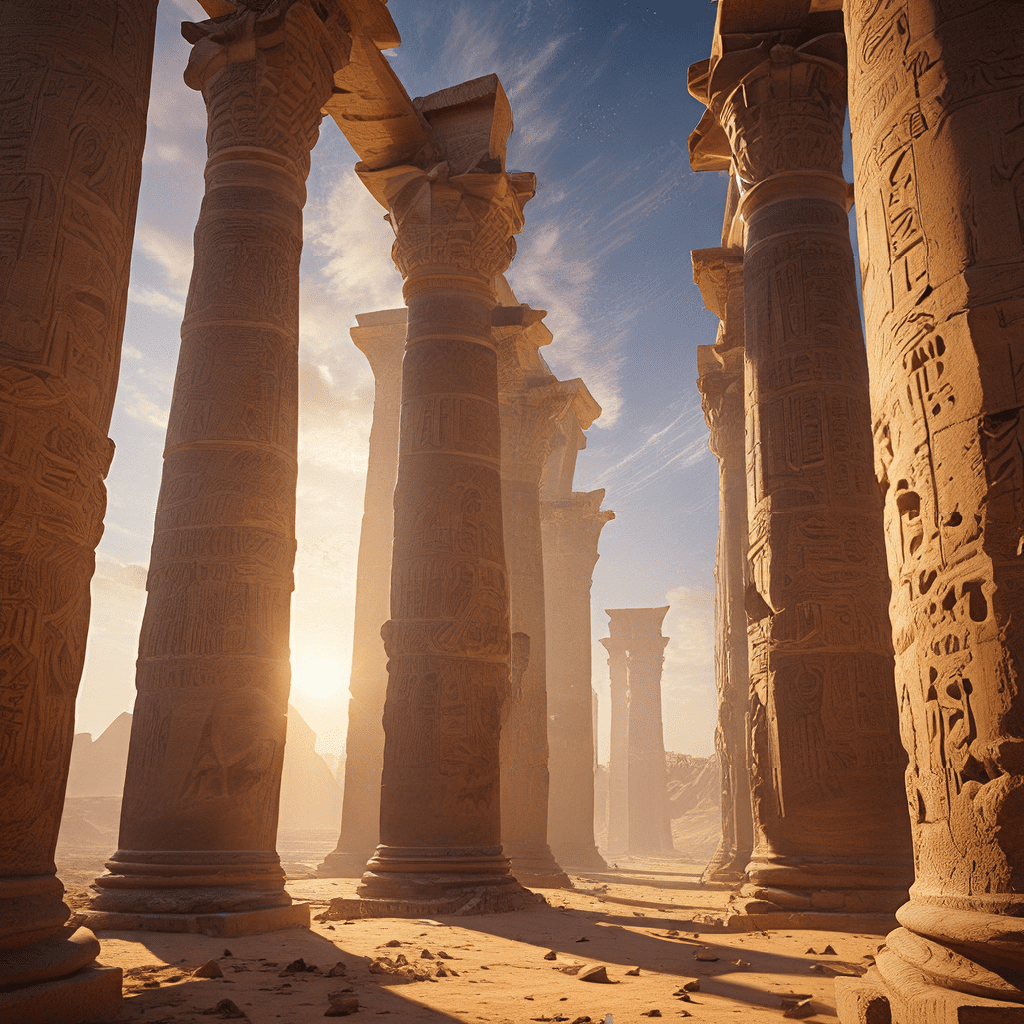

3. The Pillars of the Sky: Supporting the Universe

The pillars of the sky were not just abstract concepts but specific mountains or places that held up the celestial dome. In Egyptian mythology, these pillars were often associated with the god Shu, a powerful deity representing air and wind. Shu was believed to hold the sky up, separating it from the earth. Mountains were also seen as cosmic boundaries, gateways between the earthly and celestial realms. They were not simply geographical features but symbolic points of connection to the divine. The mythical mountain of *Benben*, often depicted as a pyramidal mound, held a special significance as the primordial hill that emerged from the primordial waters, forming the foundation of the world.

4. The Four Corners of the Earth: Defining the Boundaries

The Egyptians believed that the earth was squared, with four corners representing the cardinal directions. Each direction symbolized a specific virtue and was guarded by one of the “Four Sons of Horus”, representing order and stability. The concept of “four corners” was not just a geographical orientation but a fundamental principle of cosmic balance. It reflected the importance of order and harmony in the universe.

5. The Duat: The Underworld as a Counterpoint

Below the earth, the Egyptians imagined a realm of shadows, the *Duat*. This underworld was a place of darkness, mystery, and transformation. The deceased journeyed through the Duat after death, navigating a complex underworld filled with challenges and trials. Each stage of this journey was overseen by different gods, each possessing unique powers and roles. Osiris, the god of the underworld, ruled over the Duat, while Anubis, the jackal-headed god, guided the souls of the deceased through their final passage. The *Duat* was not a place of eternal punishment but a place of transformation, where the soul was judged and prepared for rebirth.

6. The Celestial River: The Nile as a Cosmic Connection

The Nile River was not just a source of life and sustenance for the Egyptians. It was seen as a reflection of the Milky Way, a cosmic river flowing through the heavens. It was believed that the Nile’s annual flooding was a divine act, a gift from the gods, bringing life and fertility to the land. The cyclical nature of the river’s flooding was viewed as a metaphor for death and rebirth, and a reminder of the interconnectedness between the earthly world and the cosmic realm. Egyptians even believed the Nile connected the earthly world with the underworld, providing a passage for the souls of the deceased to reach the *Duat*.

7. The Stars: Celestial Markers of Time and Destiny

The Egyptians were stargazers, meticulously charting the movements of stars and constellations. The stars were not just celestial ornaments but guides, providing navigation for travelers, regulating the agricultural calendar, and offering a framework for their myths and legends. The Egyptians believed that certain constellations were linked to specific deities, reflecting the influence of the celestial realm on human affairs. Some stars were associated with the destiny of kings, while others were believed to hold the key to understanding the cycles of life and death. The star-studded sky was a calendar, a map, and a celestial library, offering insights into the past, present, and future.