1. Introduction: The Eternal Dance of Creation and Destruction

The ancient Egyptians saw the universe as a vast and mysterious place, filled with powerful gods and goddesses who shaped their fate. Unlike many other cultures, they didn’t believe in a single, linear creation story. Instead, they saw history as a cyclical journey, a continuous dance between creation and destruction. This dance was governed by the concept of Ma’at, which represents cosmic order and balance. Ma’at was not just a concept; it was a living force, a goddess who embodied justice, truth, and harmony. This order extended to every aspect of life, from the daily routines of the people to the movements of the stars and the cycle of the seasons.

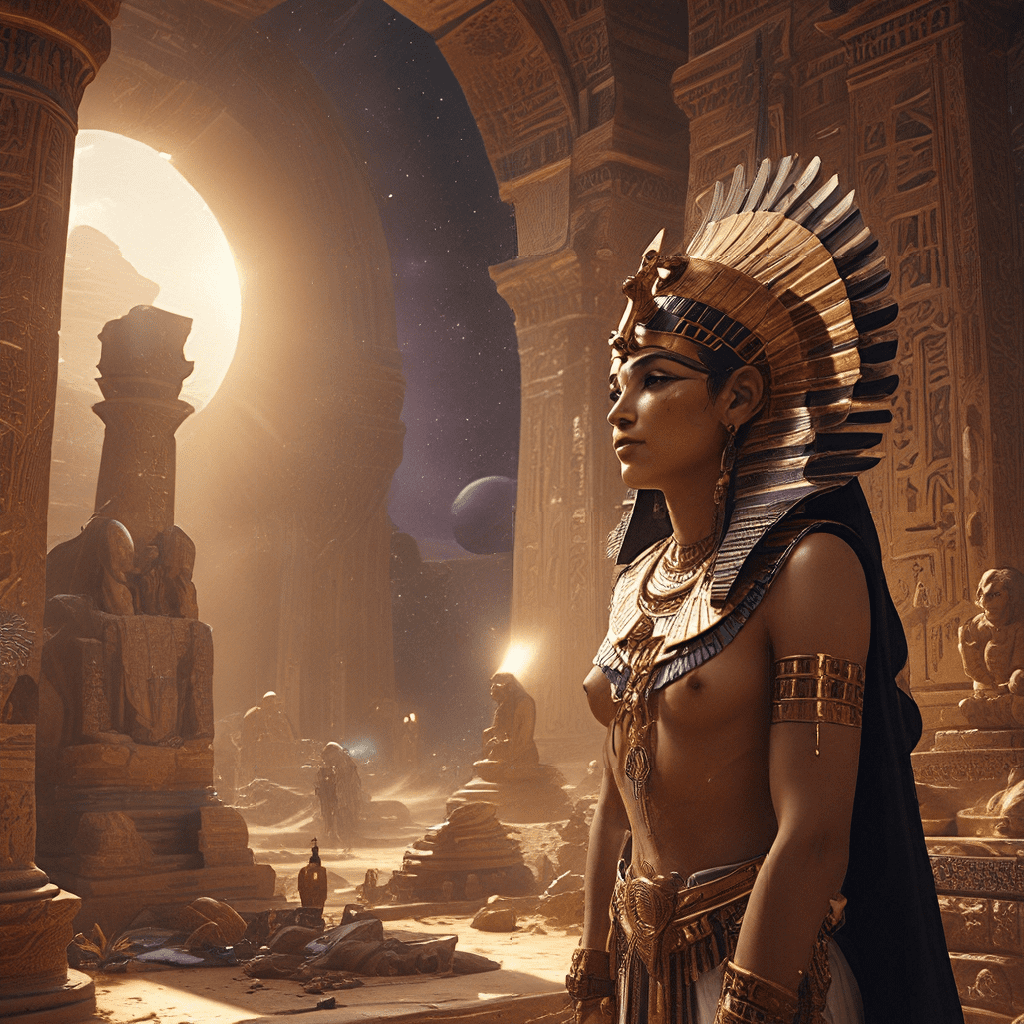

To maintain this cosmic order, the Egyptians believed that divine beings, the gods, played a crucial role. These gods weren’t simply distant figures, but actively shaped the lives of humans. They were responsible for the creation of the world, the rise and fall of empires, and even the journey of the soul after death. Understanding these divine beings and their roles was essential for the Egyptians to navigate the world around them and find their place within the grand cosmic order.

2. The Primeval Waters: From Chaos to Order

The journey of the cosmos, as imagined by the Egyptians, began with Nun, the primordial sea. Before the existence of the world, only Nun existed, a vast, chaotic expanse of water. But within this chaos, the potential for order existed. This potential manifested with the emergence of Atum, a self-created deity who emerged from the waters, representing the birth of the first being. Atum, also known as Ra, the Sun God, represented the order that came from chaos, the light that dispelled the darkness.

Atum, in a creative act, gave birth to Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), and thus the first elements of the universe came into existence. This act of creation was symbolic of the universe’s very essence – the continuous cycle of birth, growth, and renewal. The Benben, a sacred stone often depicted as a pyramid, represented the first land that emerged from the waters. This primordial mound, rising from the sea, was a symbol of creation, order, and the origin of the universe. The Benben served as a testament to the enduring power of the divine and the constant battle against chaos.

3. The Celestial Landscape: A Map of the Afterlife

The ancient Egyptians were keen observers of the sky, and their cosmology reflected a deep understanding of astronomy. The Sun God Ra’s journey across the sky, from sunrise to sunset, was seen as a daily reenactment of creation and the cycle of life. Ra sailed across the heavens in his solar boat, bringing light and life to the world. At night, Ra descended into the underworld, the Duat, where he battled darkness and chaos to ensure his triumphant return at dawn. The Egyptians believed that the stars and constellations provided a celestial map, not only of the night sky but also of the afterlife. Nut, the goddess of the sky, was seen as the celestial mother, holding the stars in her womb.

The Nile River played a crucial role in the daily lives of the Egyptians, and they saw it as a microcosm of the cosmic order, representing the journey of the sun and the cycle of life and death. The annual flooding of the Nile, bringing fertility to the land, mirrored the cycle of creation and renewal, echoing the journey of Ra through the underworld and his eventual rebirth in the morning. This interconnection between the celestial and the terrestrial world was central to the Egyptian understanding of the universe.

4. The Underworld: A Journey of Transformation

The Duat, the Egyptian underworld, was not simply a place of darkness and fear but a complex and multifaceted realm where the journey of the soul after death unfolded. It was a landscape filled with dangers and trials, a place where the deceased had to navigate through various obstacles to reach the afterlife. The deceased soul was guided by Osiris, the god of the dead, and judged by Anubis, the jackal-headed god who weighed the heart of the deceased against the feather of Ma’at, the symbol of truth and justice. This journey was not just about punishment or reward, but about transformation and rebirth.

The Egyptian belief in the afterlife was closely tied to the concept of the Ka, the spiritual essence of a person that continued to exist after death. The Ka needed a physical body to continue its journey; hence the elaborate process of mummification was crucial. The journey through the underworld was a test of the deceased’s life, a purification process designed to free the Ka from the earthly realm and allow it to join the divine. The underworld was not a place of eternal darkness but a transitional space where the soul was cleansed and reborn, ready for its final destination.

5. The Human Soul: A Complex Web of Aspects

The ancient Egyptians believed that the soul was a complex entity, not a single, unified whole, but a web of distinct aspects that worked together to form a complete person. The Ka, as we discussed, represented the spiritual essence, the life force that continued after death. The Ba was the personality, the individual’s character and unique traits. The Akh was the transformed being, the fully realized soul that achieved eternal life in the afterlife.

The Egyptians believed the journey of the soul after death was not only a physical journey through the underworld but a spiritual transformation. Through elaborate rituals and offerings, the deceased could be aided in their journey and ensure their successful transition to the afterlife. They believed that the preservation of the body through mummification was crucial as it provided a vessel for the Ka, allowing the soul to continue its journey and achieve immortality. This complex understanding of the soul and its journey highlights the Egyptians’ fascination with the afterlife and their desire to find meaning in the face of death.

6. The Divine Pantheon: A Tapestry of Relationships

The Egyptian pantheon of gods and goddesses was vast and diverse, reflecting the many aspects of nature and human experience. These gods were not just distant beings but deeply involved in the lives of humans, influencing their destiny and shaping their world. The pantheon was organized into nine eneads, families of gods that represented different realms of existence: creation, the sun, the sky, the underworld, the Nile, and more. These eneads were not isolated entities, but interacted with one another, forming a complex tapestry of relationships that reflected the interconnectedness of the universe.

The interactions between gods and goddesses were often dramatic and filled with tension, reflecting the conflicts and complexities of human life. Stories about their relationships, including creation myths, love stories, power struggles, and betrayals, provided the Egyptians with frameworks to understand the world around them. The Egyptian pantheon was a living, evolving system, reflecting the changing needs and beliefs of the people over centuries. The gods were not static figures, but constantly redefined and reinterpreted, serving as a powerful source of inspiration and guidance for the Egyptians.

7. The Role of Kingship: A Connection to the Cosmic Order

The pharaoh, the king of Egypt, was not just a political leader but also a divine figure, a living embodiment of Horus, the god of kingship. The pharaoh was seen as the intermediary between the gods and the people, responsible for maintaining Ma’at, the cosmic order. His actions had profound cosmic implications, affecting the well-being of the land and its people. The Egyptians believed that the pharaoh’s power derived from the gods, and his success in maintaining Ma’at ensured the flourishing of the kingdom.

The pharaoh’s role extended beyond earthly matters. He was also responsible for ensuring the proper functioning of the afterlife, acting as a guide for the deceased souls on their journey through the Duat. The pharaoh’s tomb was a miniaturized version of the cosmos, a reflection of his divine power and his role in maintaining the delicate balance of the universe. The connection between kingship and the afterlife was profound, reminding Egyptians that their earthly rulers were not only political leaders but also integral figures in the wider cosmic order.